New Threats for the Same Security Issues

The need to secure information is a concern at the forefront of many executives' minds, and for good reason. Every day news reports document information security incidents that cost companies significant time and money to resolve, often at the expense of their brands and reputations:

- CardSystems Solutions Inc. is poised to go out of business as a direct consequence of a May 2005 security breach in which 40 million credit card numbers stored on their internal network were accessed by attackers who defeated the perimeter security. The company announced the breach May 22nd, and on July 19th, both Visa and American Express announced that they would no longer use CardSystems Solutions.

- An angry systems administrator—who alone developed and managed his company's network—centralized the software that supported the company's processes on a single server. He then coerced a coworker to give him the only backup tapes for the software. After the systems administrator was fired for inappropriate and abusive treatment of his coworkers, a logic bomb he had planted deleted the only remaining copy of the critical software from the company's server. The company estimated the cost of damage in excess of $10 million and as a result had to lay off 80 employees.

- The MyDoom worm made it past firewalls as an email attachment in January 2004. At the height of the outbreak, more than 100,000 occurrences of the worm were intercepted each hour. Cleverly disguised as an innocuous text file attachment, unsuspecting users opened the attachment and launched the worm inside their network perimeter. In 2004, MyDoom was estimated to have cost businesses $250 million (http://money.cnn.com/2004/01/28/technology/mydoom_costs/).

- An IT sector application developer who was downsized out of his job before the Christmas holiday launched an attack on his former employer's network 3 weeks after his termination using one of his former coworker's user ID and password to obtain remote access to the internal network. He modified many of the company's Web pages by modifying text and posting pornographic images, in addition to sending each of the company's customers an email message letting them know the Web site had been attacked. He also included within the message the customers' IDs and passwords for the Web site. A month and a half later, the developer attacked again through the remote connection, this time resetting all the network passwords and changing 4000 pricing records. He was sentenced to 5 months in prison, 2 years supervised probation, and ordered to pay his former employer $48,600 in restitution.

- An upset city government employee who did not get a promotion deleted files from office computers the day before the person who got the new position started. The subsequent investigation verified the disgruntled employee as being responsible for the incident. However, the city government officials did not agree with the police detective about whether all of the deleted files were recovered. No criminal charges were filed, and the employee was allowed to resign.

Public attention has generally focused on preventing harm to networks by creating an impenetrable perimeter to keep unwanted outsiders at bay. Reality demonstrates, however, that the network is highly susceptible to threats that originate within the perimeter as well as threats that make it through a perimeter that is, in today's environment, highly vulnerable and porous and cannot feasibly be made impenetrable. Additionally, the human threats from trusted network users are increasing. For example, an authorized insider might be able to disable certain network security mechanisms to allow a collaborator on the outside to gain access. Alternatively, an insider might be able to transmit large volumes of sensitive information from inside the network to an outside destination without ever being discovered. Perimeter security has typically focused on keeping the bad things from entering the network—not preventing things from going out of the network.

Network Perimeters Are Now Like Sieves

The well-defined perimeter is disappearing, and your network is no longer like a steel fortress protecting against threats—instead it is like a stainless steel sieve. Mobile employees, wireless access, Web-based applications, remote workers, contractors, and business partners who have access to your network have put an end to the perimeter fortress. These factors can innocently or maliciously introduce attacks on the network and jeopardize confidential information and corporate assets. Attacks can come from anywhere at any time. There is no longer a well-defined perimeter.

Today, you need powerful, proactive security practices for all systems that connect to your internal network. New business demands and processes will continue to expand your perimeter, increasing the risks to your network. Without a plan to secure inside the perimeter, employee productivity, revenues, information, computing resources, and your company brand are highly susceptible to being greatly damaged. Internal security has become an obligation and a necessity. Customer confidence relies upon it, and worldwide laws and regulations require it.

Successful security requires the network to imbed security throughout the many network layers, applications, and associated devices as well as instilling effective security practices within the personnel who have trusted access to the network. Technology can be implemented to help discover when trusted network users are attempting to do damage. The time has come to pervasively secure inside the network perimeter.

Issues Are Nothing New, But the Threats Continue to Grow

Businesses have always faced numerous issues with regard to handling and protecting information. The primary issues have not changed much, but the number and types of threats created by computers and innovative technologies continue to grow. Threats to information include:

- Outsider fraud

- Insider fraud

- Employee abuse of trust

- Mistakes

- Poorly constructed applications

- Lack of due diligence resulting in protection gaps

- Lack of understanding and training

- Downsizing

- Outsourcing

- Natural causes (Earthquake, flooding, fire, and so on)

Outsider Fraud

Having swindlers try to defraud businesses is certainly nothing new; fraud has been around as long as history has been recorded. However, the techniques by which fraud now occurs is much more varied than ever before and takes advantage of new technology and human foibles. The Choicepoint fraud incident from February of 2005 is a perfect example. The fraudsters took advantage of technology to create identities based upon those of other legitimate persons, then took advantage of the vulnerabilities within the Choicepoint identity verification process to perpetrate a fraud against the company while compromising the security of 145,000 of the individuals within the Choicepoint databases. Phishing is another example of using technology (emails and Web sites) to commit fraud against people to whom bogus messages are sent.

Insider Fraud

The occurrences of employees with authorized access to network resources committing fraud are likely to continue to increase—although it's difficult to ascertain the current numbers for such crimes because they are under-reported to law enforcement and prosecutors (Source: National Research Council, Computer Science and Telecommunications Board, Summary of Discussions at a Panning Meeting on Cyber-Security and the Insider Threat to Classified Information, November 2000). Organizations are often reluctant to make such reports because of insufficient level of damage to warrant prosecution, a lack of evidence or insufficient information to prosecute, and concerns about negative publicity.

Employee Abuse of Trust

Employees with authorized levels of trust pose a great threat to the network when they become dissatisfied with their jobs or are otherwise motivated to take advantage of their extensive access capabilities and have a desire to cause damage on the network. Growing numbers of cases of disgruntled IT systems administrators modifying files and making business networks unusable have been reported.

Mistakes and Errors

Mistakes, errors, and omissions by insiders within the network perimeter are some of the most prevalent causes of information security problems. Accidentally sending email to the wrong person can lead to a loss of confidentiality if these messages are not protected, and loss of availability to the intended person. The most commonly cited example of this type of security breach is when an Eli Lilly employee accidentally sent an email to all Prozac users subscribing to a prescription service with all the names of the recipients clearly visible within the message heading.

Poorly Constructed Applications

A particularly common threat is through incorrectly configured or out of date security controls or exploitable software such as operating systems (OSs) and databases without up-to-date patches. Although these errors are usually accidental, programming errors can cause systems to crash. Application security cannot be delegated to the network administrator; it must be an integral characteristic of an application's overall architecture. A truly well-built application will inherently be secure. A poorly constructed application may be impossible to secure—effective security can't simply be tacked onto an application after it has been written. Application security must be addressed throughout the entire development process, not as an afterthought.

Lack of Due Diligence Resulting in Protection Gaps

Oftentimes in the rush to get a system or application into production, the implementation teams either inadequately test the security or assume someone else has performed testing for security issues. If errors or omissions are made during the software development, maintenance, or installation process, the integrity, reliability, confidentiality, and availability of the information processed could be threatened.

Using commercial off-the-shelf software does not guarantee error-free software. Hotmail had a bug that allowed anyone to read the accounts of their subscribers without a password. Microsoft Outlook and Outlook Express software had a bug that allowed malicious code to run on a computer without the knowledge of the user and cause Outlook and Outlook Express to fail. In addition, this bug allowed unauthorized individuals to utilize user access rights to reformat the disk drive, change data, or communicate with other external sites.

Lack of Understanding and Training

Many organizations do not adequately communicate their security policies and procedures to their personnel or train them for how to integrate security within their job activities. If personnel do not know how to properly implement security, they can easily perform activities in ways that put the network at risk. For example, if an employee does not know they need to secure the computer screen when away from the work area, an unauthorized person can access that system in the user's absence and commit fraud or maliciously delete or alter files—all under the authorized user's name.

Downsizing

After a company has reduced staff, it is common for people who have been laid off to be upset. Often they are given 2 weeks notice while retaining all the same rights to the network. When people know they will soon be unemployed, and are upset, they may maliciously use their access rights to wreak havoc on the network. For example, Omega Engineering suffered $10 million in losses after a network engineer, upset about being laid off, detonated a software time bomb that he had planted in the network he helped to build. The bomb made the Omega network unusable and brought the manufacturer of high-tech measurement and control devices used by the United States Navy and NASA to a standstill. When the bomb went off in the central file server that housed more than 1000 programs as well as the specifications for molds and templates, the server crashed, erasing and purging all programs. The incident resulted in 80 layoffs and the loss of several clients.

Outsourcing

The third parties to whom you give access to your network may not have the motivation or knowledge to adequately secure their activities. Also, if you connect an outsourced organization to your network, their security threats, vulnerabilities, and risks then become yours. You also risk having your information inappropriately used by employees who have no motivation to secure the information that comes from another company. For example, in 2005 a British newspaper, the Sun, reported purchasing credit card and other confidential details about hundreds of British citizens for just $5 each from an employee of an outsourcing organization in New Delhi.

Natural Causes

Environmental threats include natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes, tornadoes and other environmental conditions. These threats result in the loss of availability of information that could lead to an inability to perform critical tasks, financial loss, legal liabilities, and even loss of public confidence or image. When these threats are coupled with inadequate physical security, there is also risk of loss of confidentiality of information.

Move Perimeter Concepts Inside

Organizations must focus on securing their internal network with the same vigilance that is applied at the perimeter. Organizations can apply similar information security techniques developed for the perimeter to their internal networks including the following:

- Defending against malicious code and worms and containing their spread

- Ensuring only safe devices and endpoints access the network

- Ensuring the privacy and integrity of data in motion

- Protecting critical applications from misuse and abuse

- Establishing an effective program for patching vulnerable systems

- Educating network users about how to apply security

Urgency to Address Old Problems with New Solutions

There is an increased urgency to address old problems with new solutions. Businesses have always had to face the problems of technology evolving faster than the associated security solutions. Keeping employees vigilant with their security practices as new computing devices become ever more mobile and affordable has been challenging business leaders since the introduction of the desktop computer. What used to work is no longer effective.

Financial Impacts Are Increasing

Security incidents are causing increasingly larger financial impacts. New destructive threats continue to emerge. For example, it is widely estimated that the Slammer worm alone caused more than US$1 billion in damage. Protecting against and containing worms is currently the most pervasive problem driving investment in internal security solutions. However, there are dozens of other problems that cause significant financial impact.

Vendor Communications Drive Security Exploits

Security vulnerabilities are now communicated much more proactively and quickly by vendors than ever before. As a result, the time from vulnerability announcement to active exploits has shrunk dramatically. It never seems as though the patches for security holes can be applied quickly enough. Businesses are continually trying to find new and better ways to protect their network resources while they are susceptible to the exploits until the software security patches can be applied.

Network Endpoints Are No Longer Managed Centrally

New types of technologies and devices are creating cavities within the network perimeter often without the notice of the organization. Organizations must realize that endpoint devices—such as personal computers, PDAs, Blackberries, and smart phones—must be secure on the networks as well as when they are connecting from outside the perimeter, such as through a VPN or wireless connection. If these endpoints are not secure, they can easily inadvertently introduce malicious code and other security threats to the organization.

Business Leaders Must Shift Their Security Approach

A June 2005 study inquired 140 top enterprise and government security executives about their approaches to network security and budget trends. This study revealed the need for tighter user access controls and continued concern about security threats and patching, even though the security budgets had increased in most of the organizations. Surprisingly, the study also found that more than half the respondents are still relying upon the perimeter as the primary way to protect the internal network, providing unmonitored access to the network resources once a user is authenticated. Sixty-two percent acknowledged that their organizations faced intrusions from internal sources that were authorized to be there.

It is essential that the network perimeter must be secured as much as possible. However, just relying upon perimeter security will not save organizations from costly security incidents, such as the attacks that have been widely reported against credit card processing centers and banks. There is an immediate need to make security a pervasive feature of all components of the network, inside and out. Access to the network must be pre-emptive as well as proactive and reactive.

Leaders Must Plan for Security Incident Response

It is also essential to plan ahead how an organization will react to internal security incidents and breaches. Many organizations are not prepared. The ways in which organizations respond to incidents and breaches typically fall into one of approaches:

- Locking down the affected sections of the network completely as soon as there is a significant security event

- Shutting down the entire network completely when an event occurs

- Turning on monitoring, quarantining, and blocking right away

- Reacting chaotically in an ad hoc manner with no clear direction or plan

Most organizations patch the perimeter and external servers much more quickly than the internal network resources. Because the resources are internal, most business leaders assume they can take much more time to apply the security patches because the perception is that the risks are much lower within the perimeter.

Leaders Must View Network Security Differently than in the Past

Organization leaders need to start thinking about network security from a perspective other than the old outside, perimeter, and internal way. Organizations need to take into consideration the following issues with regard to the components of their network:

- Which components are the high-value targets for an attack?

- Which components would have the most business impact if they were breached or made unavailable?

- What strategies should be used to efficiently and quickly respond to incidents?

- Is there information being stored or processed in inappropriate and insufficiently secured locations within the network?

- What human and managerial approaches should be used to defend against existing threats to all areas of the network?

- What changes in the security business model must be made to address the changes within technology that by their construct create new vulnerabilities, such as wireless, peer-topeer, and mobile computing?

- Is the quality of the applications sufficient to help deflect attempted security breaches?

Information Security Market Immaturity Creates Challenges

Another challenging aspect of today's environments is that the information security market is still in its infancy. There are very few formal standards established for security products or services. Many vendors offer individual solutions such as firewalls that address only one type of security need. Organizations are challenged with making disparate and widely ranging types and qualities of security solutions work together, creating patchwork security across the enterprise. IT staff bears the daunting task of cobbling all these solutions together, constantly deploying an expanding list of products and spending inordinate amounts of time and money completing the integration work to ensure that these components are working together. These immaturity issues create other significant challenges for IT staff:

- IT staff must absorb huge amounts of information to understand and manage the computing environment. Each product generates alarms, logs, and other information that they must review to determine whether something is wrong.

- The software industry places relatively low priority on security. Although some vendors garner a lot of press by announcing their concern and emphasis on security, most do not follow this example or go far enough with deploying security features. In fact, security is often sacrificed to make the software easier to use and less costly, resulting in growing numbers of vulnerabilities.

- Information security vendors will not offer mature solutions to adequately protect business any time soon. Businesses must develop strategies to mitigate risks for their own unique threats, risks, and vulnerabilities instead of depending upon a silver bullet solution to quickly provide resolution.

Scalability Issues

The nature of the internal network environment presents unique challenges when compared with perimeter security. Quite simply, when considering both, internal security requires significantly greater:

- Scale of the environment—Protection requires numerous networks, sub-networks and potentially thousands of systems.

- Scope of the environment—There are significantly greater, widely varying business applications and underlying protocols—not just HTTP, FTP, SMTP, and the handful of others associated with the DMZ.

- Numbers of users—The number of individuals and groups authorized to use the internal network is much more than with the external environment where there are typically very few defined groups with limited access privileges. Internally, the different roles can easily number in the hundreds or thousands, resulting in a much more complicated set of policies and controls.

- Speeds and volumes of traffic—Internet connections and associated DMZ resources rarely face more than 45Mbps, while internal networks and systems routinely operate at two to ten times that bandwidth. As a result, any controls that are implemented in the internal environment need to be capable of conducting the necessary inspections and dispositions at a much greater rate.

Table 1.1 compares the concerns of internal versus perimeter security.

Concern | Internal Security | Perimeter Security |

Network Issues | Thousands of systems to protect | Small number of systems to protect |

Hundreds of thousands of Mbps of traffic to monitor | Tens of Mbps of traffic to monitor | |

Application Issues | Thousands of applications | A dozen or so applications |

Hundreds of thousands of protocols | Few protocols | |

In-house applications | Standardized and well-defined applications | |

Protocol compliance more lax | Strict adherence to protocols | |

Client-to-client applications | Client-to-server applications | |

Remote connections |

| |

Dependency on end users for many controls |

| |

Management Issues | Hundreds to thousands of user and group roles | Few user and group roles |

Monitor the unknown or unusual | Block the unknown of unusual | |

Decentralized coordination | Centralized coordination | |

Resource Issues | Large number of IT staff to support | Typically small IT support team |

Small ratio of security to network size budget | Large ratio of security to external IT components budget |

Table 1.1: Internal vs. external security scalability.

Making Internal Security Scalable

How can an organization position network security solutions to accommodate change while not, or at least not noticeably, impacting network performance? What type of incremental cost for security must be accepted in order to adequately secure all components of the network according to their level of risk? Organizations need to consider the scalability issues involved with security when designing not only their security architecture but also their entire network infrastructure.

Let's look at a few examples of how architecture components within a business network impact the security scalability challenge.

Types of Routers

Most organizations buy the least expensive routers to meet their business and security needs of the moment. However, buying modular routers, even though more expensive up front, might be better than buying fixed-configuration routers because it is more efficient and easier to add and modify user and network interfaces, when needed, at a lower incremental cost. Security scalability is impacted by such issues as the type of router used, the size of the network, router configuration files, and the audit files generated.

Server Selection

Most organizations purchase servers to meet their current and existing business processing and security needs. Consider how well the server you choose will scale to handle your company's specific processes, such as online transaction processing (OLTP). It may be better in the long run to invest in a multi-processor-ready server even if you only need one processor for your current business. As your transaction load increases, you can then add more processors as necessary at a lower price. Security scalability is impacted by such issues as access control files and directory permission structures.

Network Design

Have you integrated all your organization's needs for voice, data, and high-speed dedicated Internet access across your network using an integrated service provider (ISP)? Determine whether the ISP is capable of adding bandwidth for both access and long-haul transport as your business needs change. Determine whether the ISP can support IP, Frame Relay, and ATM as required to meet performance objectives. Security scalability is impacted by such issues as firewall port configurations, instructions detection devices, audit files, and encryption configurations.

Zoning Helps Address Scalability Issues

Establishing enterprise-wide security zones helps to address the security scalability issues. Security zones not only support the effectiveness of layering security but also decreases the cost of enterprise technology infrastructure and create a scalable environment. Enterprise-wide security zones also support open architectures and encourage more collaboration and teamwork within and across the enterprise, addressing the management challenges of such collaborations. The significant movement toward embracing cooperation across organizations and sectors creates security problems. However, establishing security zones allows organizations to more successfully collaborate with one another while still protecting their valuable information resources.

Security Must Be Scalable as well as Support Business Goals

The challenge with creating scalable security architecture is building it effectively to allow the enterprise to function as it needs to meet business goals. The security solution must be scalable to give the organization what it needs for adequate security. Successfully scalable security solutions result from the security planners and implementers understanding both the business and the risk, threat, and vulnerability environments in detail. Many inefficient and rigid security solutions have been built because the organization did not consider the business and built the wrong security architecture.

The mix of security technologies used impacts scalability. Before implementing each separate security solution based solely upon the narrow scope of the task(s) it performs, you should ask some questions:

- What set of tools, technologies, and strategies comprise effective security practice for your specific organization?

- Is it possible to reduce this set of separate components into a set of business rules?

- Do these components support your existing security standards? Or, do you need to establish security standards?

- Is the technology you are considering mature? Is implementation or application within your environment going to be optimal compared with other technologies?

- What other security mechanisms are already deployed? How will the technologies under consideration interact with them? Will they conflict or enhance security?

- Is implementation of the security technology user friendly?

Business networks are often very limited in scalability because current tools are used with other tools that are not compatible, difficult to implement, a challenge to administer and maintain, and are poorly managed.

Multi-National Issues

Multi-national business drivers are prompting more focus on internal security than ever before, making security within the perimeter a priority. Companies must comply with world-wide regulations to ensure the privacy of their customer information as well as the security of the intellectual property that resides on internal networks. These global requirements drive an increased need for internal security.

There is also an increased awareness about malicious network attacks on internal networks that can be launched from anywhere in the world. Organizations in the past took an approach of not telling when incidents occurred to avoid the publicity and potential resulting negative business impact. However, now it is required by many international laws for organizations to provide proof that they are adequately protecting their entire network and the personal information stored within. This requirement is made even more significant as the number of internal attacks increases.

The Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu 2005 Global Security Survey shows internal attacks on information technology systems are surpassing external attacks at the world's largest institutions. The survey revealed that 35 percent of respondents confirmed attacks from inside their organization within the past 12 months, up from 14 percent in 2004.

There are many legal aspects to ensuring the security of information within the perimeter. Privacy and workplace surveillance issues need to be addressed when determining how, within an organization, to implement tools to decrease the possibility of insider malfeasance.

Technology that produces data (audit logs, for example) that meet acceptable legal and forensic standards must also be addressed. In addition, monitoring and termination requirements for individuals suspected of internal network abuse or misuse must be addressed under the requirements of employment laws while also meeting the needs for systems security. Finally, sophisticated adversaries can take advantage of jurisdictional differences and route their attacks through non-cooperating jurisdictions. The jurisdictional challenges are complicated by the fact that under United States' law search warrants are geographical in nature. The restrictions on cross-border data flow impacts how a geographically dispersed world-wide network can share data among different network segments.

Controls Must Address International Requirements

International network controls must ensure that risks are reduced to an acceptable level by taking into account:

- Requirements and constraints of national and international legislation and regulations

- Organizational objectives

- Operational requirements and constraints

- Cost of implementation and operation in relation to the risks being reduced and remaining proportional to the organization's requirements and constraints

- The need to balance the investment in implementation and operation of controls against the harm likely to result from security failures.

Insider Attacks

Insider attacks might be difficult to prosecute in certain countries. For example, in Australia, an internal security breach occurs when an employee of a company uses the company's information system without authorization or uses it in such a way that exceeds his or her valid authorization. Consider a couple of related court cases:

- In the 1993 Victoria case DPP v. Murdoch, the defendant was prosecuted for computer trespass under the Summary Offences Act. The judge ruled that the relevant computer offense provisions of the act do not distinguish between persons who have no permission to enter a computer system and persons (such as employees) who have authority of some kind to enter the computer system, "If [an employee] has a general and unlimited permission to enter the system then no offense is proved. If however there are limits upon the permission given to him to enter that system, it will be necessary to ask was the entry within the scope of the permission? If it was, then no offense will be committed; if it was not, then he has entered the system without lawful authority to do so."

- In the 1995 New South Wales case of Gilmour v. DPP, the Supreme Court applied the above principle and held that an entry of data is made "without authority" when the employee is not authorized to make the particular entry, notwithstanding that the employee has general authority to gain access to the computer and make other entries.

Worldwide Legislation Spans Broad Areas

Because the Internet is easily accessible from any location in the world and most large organizations are now multi-national, it is important to understand and operate in compliance with worldwide regulations. Just a few examples of international legislation that is stricter with regard to data protection requirements than many United States laws include:

- The European Union Data Protection Directive

- Canada's Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

- Japan's Personal Information Protection Act

- Australia's Federal Privacy Act

An important consideration for business executives to remember is that laws and regulations are generally enacted on a country-by-country basis while electronic commerce is performed globally. As soon as your business uses the Internet to conduct business, you are doing business with the world. This consideration has the tremendous advantages of offering your products and services globally; however, you also need to comply with local regulations. These regulations are by no means consistent, and you could easily find yourself conflicting with one regulation by complying with another.

One major challenge with global electronic commerce and network sharing is that certain countries do not place a high priority on protection of personal information or intellectual property. They might have higher priority issues, such as food or medicine, and might be unwilling or unable to police individuals who are engaged in activities such as software piracy. Computer criminals typically operate freely in these countries without the fear of law enforcement agencies shutting down their operations. Unless business executives put strategies in place to protect their intellectual property and customer information, they run the risk of falling victim to these individuals.

Addressing Compliance Issues and Requirements

One example of a United States' Federal law is the Sarbanes-Oxley Act that went into effect in July 2002. It is intended to protect investors by improving the accuracy of corporate disclosures. All companies publicly traded in the United States must meet financial reporting and certification mandates for all financial statements. From an information security perspective, it is difficult to achieve compliance under Sarbanes-Oxley without having an effective information security program to protect your vital financial information.

- Adequate controls must be implemented to ensure that only authorized individuals are able to access this information.

- Change control processes must be in place to ensure that any changes to your financial systems are implemented in a controlled manner.

- A business resumption program must be in place to ensure that your organization can continue to operate in the event of a disaster.

Legislating State-Level Security

One example of state-level security legislation is California Senate Bill (SB) 1386, which went into effect in July 2003. It requires organizations that have customers or consumers in California to disclose any breach of security related to specific types of personal data, including Social Security numbers, drivers' license numbers, and account, credit, or debit card numbers. Security breaches include unauthorized access of computer data that compromises the confidentiality or integrity of that unencrypted personal information. Individuals who are affected by this breach of security must be notified. Most states now have pending similar legislation, and many have already signed similar bills into law.

Companies Need to Report Breaches

Public notification and reports to government of security breaches can be embarrassing to companies and can have a direct impact on their brand and revenue stream. However, penalties can be imposed on organizations that do not comply with the notification requirements. These regulations place additional importance on having an effective information security program, including comprehensive internal controls in place.

With the growing number of e-commerce security incidents, the number of regulations will continue to increase. It is important to understand these laws and the restrictions that they can pose to your information security program. Successful business executives will develop strategies that turn these challenges into competitive advantages.

Businesses Must Be Prepared to Respond to Breaches

Organizations must have a plan for responding to such legal requirements for reporting and breach notification. They must also educate their employees about how to address such issues as well. Unfortunately, this communication does often not occur, although it is crucial, as evidenced by the 2005 E-Crime Watch survey conducted by CSO Magazine in cooperation with the United States Secret Service and the CERT Coordination Center, which reported "The respondents rated employee security training, education and awareness programs, and regular communication as the most effective strategies for deterring insider threats. These strategies create a culture of security in the organization, where all employees understand that security is a shared responsibility."

With more and more laws requiring breach notifications to impacted individuals, organizations must make it a priority now to plan on how to both identify when a breach has occurred and how the breach response will be handled. Organizations cannot simply hope that a breach will not happen to them.

Business Is Impacted by Insiders Committing Security Breaches

Although an employee who commits an internal network attack will often face criminal prosecution, the organization might also end up being the subject of a civil lawsuit. A very significant danger exists to organizations regarding insider network security breaches committed by an employee who uses the organization's computer systems to commit electronic fraud or cause damage or loss to third parties. In these situations, it's possible that the company could be held liable for the acts of its employee. This risk is just one more of many reasons the network must be robustly secured within the perimeter.

All Security Incidents Impact Business

Many CEOs and CIOs are slow to invest in computer security because they do not think they will get a return on their investment. What they need to consider are the costs of not investing in computer security:

- The head of CardSystems Solutions, Inc., which was infiltrated by computer attackers exposing as many as 40 million credit card holders to possible fraud, told the United

- States Congress in July 2005 that the company is "facing imminent extinction" because of its disclosure of the breach and the industry's reaction to it. Visa USA and American Express announced after investigating the breach at CardSystems' Tucson, Arizona facility that they would no longer allow the firm to process transactions made with their cards.

- According to the Carlsbad, California research firm Computer Economics, the damage from Nimda is estimated at $635 million, while Code Red cost businesses a whopping $2.6 billion.

- In December, 1998 Ingram Micro, a PC wholesaler, had to shut down its main data center in Tucson, Arizona. Ingram's Internet business and electronic transactions were down from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM. As a result of its one day of lost sales and system repairs, Ingram estimates that it lost a staggering $3.2 million (Salkeyer, Alex. "Who Pays When a Business Is Hacked?" Business Week Online: Daily Briefing, May 23, 2000. URL: http://www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/dnfarch.htm). This figure is comparable to Forrester's projection that an auto manufacturer unable to get tires for a week would lose $21 million.

Security Breaches Are Expensive in Many Ways

The value of a security breach can be measured by both tangible and intangibles considerations. The tangibles can be calculated based on estimates of:

- Lost business as a result of unavailability of the breached information resources

- Lost business traced directly to lost customers

- Lost productivity of the non-IT staff who cannot work up to usual goals while the IT staff tries to contain and repair the breach

- Labor and material costs associated with the IT staff's detection, containment, repair, and reinstallation of the breached resources

- Labor costs of the IT staff and legal costs associated with collecting forensic evidence and prosecuting the attacker

- Public relations consulting costs to prepare statements for the press and answer customer questions

- Increases in insurance premiums

- Legal costs for defending the business in liability suits resulting from failure to deliver assured information and services

- Impact of breach disclosure on stock price

Intangibles refer to costs that are difficult to calculate because they are not directly measurable, but are still very important for business. Intangibles are often related to a loss of competitive edge that results from the breach. For example, a breach can affect an organization's competitive edge through:

- Customers' loss of trust in the organization

- Failure to win new customers because of the bad press associated with the breach

- Competitor's access to confidential or proprietary information

Forrester Research estimated the tangible and intangible costs of computer security breaches in three hypothetical situations (Howe, Carl; McCarthy, John C.; Buss, Tom; and Davis, Ashley. "The Forrester Report: Economics of Security", February, 1998). They found that if thieves illegally wired $1 million from an online bank, the cost impact to the bank would be $106 million. They estimated that if network compromises were used to prevent a week's worth of tires from being delivered to an auto manufacturer, the auto manufacturer would lose $21 million. They estimated that if a law firm lost significant confidential information, the impact would be close to $35 million.

Gumball Security No Longer Works

Historically, organizations have used the gumball approach to securing networks, making the perimeter like a hard outer impenetrable shell, while leaving the inside of the network soft and chewy with less vigorous security in place. Most organizations today still primarily use the gumball approach, protecting their networks from unauthorized access by implementing perimeter protection devices, such as screening routers and secure gateways.

The threat of attack comes from two major directions: attacks based outside the corporate network and attacks based from within.

The gumball approach, although at one time effective, no longer works. When the perimeter could be well defined, it addressed the "attack from without" scenario. However, the perimeter is now very porous, with mobile computing devices, wireless access, and peer-to-peer and business-to-customer network connections poking ever more holes into the once hard shell. Even if the perimeter was not so porous, such a model cannot address the attacks from within.

Existing perimeter security does not protect from an attack from within.

IT security administrators have long focused on securing the network perimeter. Focusing on the perimeter is indeed important. However, the internal networks must be secured with the same level of diligence to reduce the risks created from the sharp increase of worms and other attacks specifically introduced inside the network via mobile and wireless devices, in addition to attacks originating from trusted network users.

Although many of the same principles used to establish and implement perimeter security solutions also apply to internal networks, internal security is generally more complex, requires elevated performance, and has requirements completely unique from perimeter security.

Existing perimeter security solutions, such as patches, antivirus software, switch and router-based solutions, legacy firewalls, and intrusion detection and prevention systems, are inadequate for comprehensive security and leave huge gaps for securing internal systems.

Organizations must increase their efforts to improve the protection inside the walls of their organization. However, the struggle to balance decreasing budgets and personnel resources result in the persistence of reliance upon the gumball approach to securing networks.

Computer Evolution Has Changed Security Needs Greatly

In the late 1960s, networks only existed in the sense of huge mainframes and hundreds to thousands and millions of networked dumb terminals connected via hubs and concentrators to the huge central processing units (CPUs) in a central, air-conditioned, properly humidified windowless room. Network security was not really a significant issue. However, in 1973, business leaders started to take note when executives at the Equity Funding Insurance Company used computers to create 64,000 fake customers; a fraud that resulted in losses of two billion dollars, to commit what is widely still considered as the biggest computer crime that has yet occurred (Donn B. Parker, Fighting Computer Crime, pg. 65, Wiley, 1998). This incident illustrates the initial threats to network security, which at the time were strictly internal, but foreshadowed the nature of most threats to come. The environment for network security was evolving.

In 1969, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) along with four computer institutions started to design a network through which data could be passed and received. UCLA, the University of California at Santa Barbara, the University of Utah, and the SRI collaborated to create ARPAnet, which evolved to the Internet.

The 1980s introduced personal computers (PCs) and local area networks (LANs), laying the foundation for more network security threats than ever anticipated. The government addressed what they perceived as eminent security issues and created security guidelines published within Trusted Computer Security Evaluation Criteria that mainly dealt with security problems for standalone machines but not network security. In the fall of 1988, the Morris worm was launched, and all of the 60,000 computers on the Internet were crippled for two entire days.

Today Security Must Be Designed to Address Global Issues

Businesses typically design business infrastructure around network architectures. Global business requires networks that link multiple businesses together. The Internet has grown to connect easily more than two million computers on one massive and primarily uncontrolled network. Corporate networks are merging with the Internet to develop Internet businesses, Webbased business transactions, and much more. Consequently, the security matters are incredibly huge. Securing just the perimeter is not enough; internal security must be robust.

What is internal security? Internal security is a focused effort to appropriately secure all resources on internal networks. Examples of resources include applications, data, servers, and endpoint devices.

Internal security attacks can happen either maliciously or inadvertently. The impact of internal security events will have a negative result on an organization from both a technical and business perspective. Organizations must take the necessary steps to secure their internal networks, not just the perimeter.

Addressing Security Within the Perimeter

Attackers have new techniques for bypassing perimeter security barriers. This is often accomplished in many ways, a couple of which include:

- Tricking inside users and systems to execute code containing worms, which then spread to other systems behind the firewall.

- Tricking users of JavaScript and ActiveX to execute malicious code hidden in external Web sites.

These internal threats in many ways are more dangerous compared with external threats because they are difficult to detect and prevent.

What Are Internal Threats?

Network perimeter security mechanisms, although necessary and effective in stopping external attacks, cannot provide sufficient protection against all outside threats or internal threats. Several threat categories were described earlier—what specific types of threats are there to the internal network?

- External email and Web browsing—Attacking a user through email and Web browsing using a variety of security flaws in commonly used scripting languages. Users are often unaware when a script is being run because scripts can piggyback on most types of data files. Often, but certainly not always, such inside-out attacks rely upon a user performing an action such as opening an attachment. Attackers may create the malicious code themselves to ensure that it will not be detected by an antivirus tool.

- External attacks using new vulnerabilities—Attacking the software and servers that are visible from the Internet. The most recent attack might be used so that it will not be detected by intrusion detection systems. Attackers frequently target email servers, domain name servers, Web servers, routers, and computer security devices such as firewalls.

- Application-layer exploits—Examples include worms and blended threats such as Sasser, Blaster, Bugbear, Slammer, and SoBig. The majority of the SANS/FBI top 20 vulnerabilities to Internet security are categorized as application-layer weaknesses. Attacks against these vulnerabilities more easily bypass perimeter security, which is typically focused on the network layer.

- Modem use—Although not used as much as in the past, modems still create an entryway into networks and are still used as backdoors to the network.

- Virtual private networking (VPN) technology—VPNs are increasingly used to connect business partners, bringing with them all the security risks and vulnerabilities that exist on the business partners' networks.

- Various user-friendly pervasively used computing technologies—PDAs, Blackberries, laptops, wireless LANs, and other popular personal computing devices are often not adequately secured but create new pathways into the internal network.

- Mobile and telecommuter solutions—Such out-of-facility work arrangements have seen widespread and increasing deployment on the basis of reducing operational costs and improving employee satisfaction. However, establishing such remote work with connections to the internal network inherently puts the internal network at risk from the remote threats.

- Code exploits—Software flaws, noticeably buffer overflows, are often exploited to gain control of a computer or to cause it to operate in an unexpected manner. The code exploits often come in the form of Trojan horses, such as non-executable media files that are disguised to function in the application.

- Eavesdropping—Any data that is transmitted over a network is at some risk of being intercepted or even modified by an unauthorized network user.

- Social engineering and human error—Malicious individuals have often penetrated well-designed, technically secured computer systems by taking advantage of the carelessness or lack of knowledge of trusted individuals, or by deliberately deceiving them, for example by sending phishing type messages.

- Denial of Service (DoS) attacks. Although such attacks are not primarily a means to gain unauthorized access or control of a system, their design to overload the capabilities of a machine or network and make it unusable can have dramatic business impact.

- Indirect attacks—These are attacks launched from third-party computers that have been taken over remotely often referred to as "zombie computers." Such attacks make it very difficult to track the originator of the attack.

- Backdoors—These threats are typically programmed methods of bypassing normal authentication or giving remote access to a computer to someone who knows about the backdoor while remaining hidden to casual to others.

- Direct access attacks—Common consumer devices can be used to transfer data surreptitiously. When someone gains physical access to a computer, all manner of devices can be installed to compromise security, including OS modifications, software worms, keyboard loggers, and covert listening devices. The attacker can also easily download large quantities of data without notice onto storage devices, such as CDs, DVDs, USB keydrives, digital cameras, and digital audio players.

Identifying Internal Security Requirements

It is essential that an organization identify all security requirements in the context of how those requirements impact business with regard to existing risks, threats, vulnerabilities, and legal and contractual requirements. Alternative paths into organizations, along with application-layer attacks, are increasing the threats that emphasize the need to complement perimeter security with a comprehensive and pervasive range of internal security activities and tools. At a high level there are three main ways to identify security requirements inside the perimeter.

- Assess risks to the organization, taking into account the organization's overall business strategy and objectives. A risk assessment will identify threats to assets and network components and evaluate the vulnerability to and likelihood of occurrence.

- Identify legal, statutory, regulatory, and contractual requirements with which your organization, trading partners, contractors, and service providers must comply.

- Take into consideration the particular set of principles, objectives, and business requirements for information processing that your organization has developed, formally or otherwise, to support its operations.

Choosing Security to Address Internal Threats

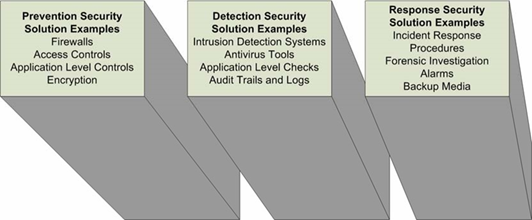

Computer security solutions generally use prevention, detection, or response to address threats, reduce risks, and address existing vulnerabilities (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Example security measures.

The following is a laundry list of example actions that can be applied to address the security risks within the internal enterprise network:

- Maintain security on internal enterprise systems. Don't think that because the internal network is behind a firewall that it is implicitly safe. Keep up to date with security fixes for all systems.

- Protect critical infrastructure systems. Critical enterprise servers such as file servers, DNS servers, and antivirus systems must receive extra attention to keep them protected. Consider what would happen if your internal DNS servers became unavailable; would all of your applications also fail? Would you be able to access systems to perform remedial work?

- Use highly securable OSs for critical functions. If this is not possible, apply stringent security measures to harden the OSs you use.

- Don't allow all outgoing traffic through firewalls by default. As with incoming traffic, you should only allow those services that you need to go out.

- Run an intrusion detection system on your internal networks but don't rely on it to detect all problems. An intrusion detection system will help you identify the threats on your network but it won't protect your network by itself.

- Carefully use firewalls or other technologies to segment internal networks. Be sure you have considered the levels of protection and how much work it will take to maintain your segmentation. Be careful not to create a single point of failure within the internal network.

- Protect VPN endpoints with firewalls, and potentially with intrusion detection system monitoring as well. A VPN from outside should never terminate on an unprotected internal node.

- Utilize encryption inside the perimeter to protect confidential or sensitive information.

- Monitor to ensure system access is disabled completely and in a timely manner following an employee termination.

- Establish formal grievance procedures as an outlet for insider complaints.

- Create a reporting process when a colleague notices or suspects suspect behavior.

- Enforce comprehensive password policies and computer account management practices.

- Use configuration management practices to detect logic bombs and malicious code.

- Monitor system log activity.

- Establish and monitor procedural and technical controls for systems administrator and privileged system functions.

- Provide layered security for remote access.

- Monitor compliance with backup procedures and testing recovery processes.

- Ensure procedures are in place to disable temporary employee and contractor access as thoroughly as that of permanent employees.

- Establish security zones to help scale and manage security activities.

Every network and organization is unique and must create their own internal security laundry list to incorporate into the security program based upon the requirements and risks.

Summary

The assumptions used to improve the effectiveness of a perimeter-oriented security strategy can no longer be used to adequately secure the organizational network. This guide will look at the threats, risks, and vulnerabilities within the internal network and help you to identify the activities that will work best for your environment. To successfully manage these issues, executives need to understand and address the following seven significant challenges:

- E-commerce requirements

- Increased value of personally identifiable information (PII)

- Information security attacks

- Immature information security market

- Information security resourcing

- Government legislation and industry regulations

- Mobile workforce and wireless computing

This chapter discussion demonstrates there are many different security issues involved with securing the network, and they are generally unchanged from the past. However, the number and types of threats continue to grow dramatically. The network perimeter has become so porous it is a bad business decision to depend solely, or even primarily, upon perimeter security to protect your internal network resources and assets. There are many compelling factors to consider that will convince you of the need to secure your network throughout the enterprise and not just at the perimeter. This chapter highlighted these factors at a high level. The next chapter discusses these factors in depth.